- Home

- Walking Tours

- Blog

-

St Peter's Basilica

- Altars

- Baldacchino

- Chair of St Peter

- Chapel of the Baptistery

- Chapel of the Bl. Sacrament

- Chapel of the Choir

- Chapel of the Pieta

- Crossing >

- Dome

-

Monuments

>

- Countess Matilda of Canossa

- Maria Clementina Sobieska

- Queen Christina of Sweden

- Pope Innocent VIII

- Pope Paul III

- Pope Gregory XIII

- Pope Gregory XIV

- Pope Leo XI

- Pope Urban VIII

- Pope Alexander VII

- Pope Clement X

- Pope Innocent XI

- Pope Alexander VIII

- Pope Innocent XII

- Pope Benedict XIV

- Pope Clement XIII

- Pope Pius VII

- Pope Leo XII

- Pope Pius VIII

- Pope Gregory XVI

- Pope Pius X

- Pope Benedict XV

- Pope Pius XI

- Pope Pius XII

- Pope John XXIII

- The Stuarts

- Nave

- Portico >

- Statue of St Peter

- Statues of Founder Saints

- Transept

- Tribune

- St Peter's Square

- Vatican Museums

- Sistine Chapel

-

Fountains

- Trevi Fountain

- Fontana della Barcaccia

- Fontana della Peschiera

- Fountain in Piazza Colonna

- Fountain in Piazza delle Cinque Scole

- Fountain in Piazza dell' Aracoeli

- Fountain in Piazza Nicosia

- Fountain in Piazza di S.M. in Trastevere

- Fountain of Moses

- Fountain of Neptune

- Fountains of Piazza Farnese

- Fountain of Ponte Sisto

- Fountain of the Acqua Paola

- Fountain of the Bees

- Fountain of the Cannonball

- Fountain of the Frogs

- Fountain of the Four Rivers

- Fountain of the Goddess Roma

- Fountain of the Lateran Obelisk

- Fountain of the Mask

- Fountain of the Moor

- Fountain of the Naiads

- Fountain of the Pantheon

- Fountains of Piazza del Popolo

- Fountain of the Porter

- Fountains of St Peter's Square

- Fountain of the Seahorses

- Fountain of the Triton

- Fountain of the Turtles

- Fountains of the Two Seas

- Four Fountains

- Rioni Fountains

- Street Fountains

- Venice Marries the Sea

- On This Day in Rome

-

Churches

- Chiesa del Gesù >

- Chiesa Nuova

- Lateran Baptistery

- San Bartolomeo all' Isola

- San Benedetto in Piscinula

- San Bernardo alle Terme

- San Carlo ai Catinari

- San Carlo al Corso

- San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane

- San Clemente >

- San Crisogono

- San Francesco a Ripa >

- San Giorgio in Velabro

- San Giovanni a Porta Latina

- San Giovanni dei Fiorentini

- San Giovanni in Laterano >

- San Girolamo della Carità >

- San Gregorio Magno

- San Lorenzo fuori le Mura

- San Lorenzo in Damaso

- San Lorenzo in Lucina

- San Luigi dei Francesi >

- San Marcello al Corso

- San Marco

- San Martino ai Monti

- San Nicola in Carcere

- San Pancrazio

- San Paolo fuori le Mura

- San Pietro in Montorio

- San Pietro in Vincoli

- San Saba

- San Salvatore in Lauro

- San Sebastiano fuori le Mura >

- San Silvestro in Capite

- San Vitale

- Sant' Agnese fuori le Mura

- Sant' Agnese in Agone

- Sant' Agostino

- Sant' Alessio

- Sant' Anastasia

- Sant' Andrea al Quirinale

- Sant' Andrea della Valle

- Sant' Andrea delle Fratte

- Sant' Antonio dei Portoghesi

- Sant' Apollinare

- Sant' Eustachio

- Sant' Ignazio di Loyola

- Sant' Ivo alla Sapienza

- Santa Caterina dei Funari

- Santa Cecilia in Trastevere

- Santa Costanza

- Santa Croce in Gerusalemme >

- Santa Francesca Romana

- Santa Maria ad Martyres

- Santa Maria degli Angeli

- Santa Maria dei Miracoli

- Santa Maria del Popolo >

- Santa Maria del Priorato

- Santa Maria della Pace >

- Santa Maria della Vittoria >

- Santa Maria dell' Anima

- Santa Maria dell' Orazione e Morte

- Santa Maria dell' Orto

- Santa Maria di Loreto

- Santa Maria in Aracoeli >

- Santa Maria in Campitelli

- Santa Maria in Cosmedin

- Santa Maria in Domnica

- Santa Maria in Montesanto

- Santa Maria in Trastevere >

- Santa Maria in Via

- Santa Maria in Via Lata

- Santa Maria Maddalena

- Santa Maria Maggiore >

- Santa Maria sopra Minerva >

- Santa Prassede

- Santa Pudenziana

- Santa Sabina >

- Santa Susanna

- Santi Apostoli

- Santi Cosma e Damiano

- Santi Domenico e Sisto

- Santi Giovanni e Paolo

- Santi Luca e Martina

- Santi Nereo e Achilleo

- Santi Quattro Coronati

- Santi Vincenzo e Anastasio

- Santissima Trinità degli Spagnoli

- Santissima Trinità dei Pellegrini

- Santissima Trinità di Monti

- Santissimo Nome di Maria

- Santo Stefano Rotondo

- Palatine

- Forum

-

Ancient Monuments

- Aqueducts

- Ara Pacis

- Arch of Constantine

- Arch of the Money-Changers

- Arch of Janus

- Aurelian Walls

- Baths of Caracalla

- Baths of Diocletian

- Castel Sant' Angelo

- Catacombs of Domitilla

- Circus Maxentius

- Circus Maximus

- Colosseum

- Column of Marcus Aurelius

- Column of Trajan

- Forum of Augustus

- Forum of Trajan

- Mausoleum of Augustus

- Nymphaeum

- Pantheon

- Ponte Fabricio

- Ponte Milvio

- Ponte Rotto

- Ponte Sant' Angelo

- Porta Maggiore

- Porta San Paolo

- Porta San Sebastiano

- Portico of Octavia

- Pyramid of Cestius

- Temple of Hadrian

- Temple of Hercules

- Temple of Portunus

- Theatre of Balbus

- Theatre of Marcellus

- Theatre of Pompey

- Tomb of Caecilia Metella

- Via Appia

-

Obelisks

- 'Minerveo' Obelisk

- 'Flaminio' Obelisk

- 'Matteiano' Obelisk

- 'Lateran' Obelisk

- 'Dogali' Obelisk

- 'Macuteo' Obelisk

- 'Solare' Obelisk

- 'Vatican' Obelisk

- 'Agonalis' Obelisk

- 'Sallustiano' Obelisk

- 'Quirinale' Obelisk

- 'Esquiline' Obelisk

- 'Pinciano' Obelisk

- 'Mediceo' Obelisk

- 'Torlonia' Obelisks

- 'Mussolini' Obelisk

- 'Marconi' Obelisk

-

Mosaics

- Gallery

- Palazzi

- Galleries & Museums

- Piazzas

-

Miscellaneous

- A Calendar of Saints

- A Literary Tour

- Antico Caffè Greco

- Art of the Cosmati

- Babington's Tea Rooms

- Barberini Bees

- Gian Lorenzo Bernini

- Borromini & the Baroque

- Catacombs

- Column of the Immaculate Conception

- Domes

- Equestrian Statues

- EUR

- Fasces

- Flood Plaques

- Funerary Monuments

- House of the Owls

- Jewish Ghetto

- Jubilee Years

- Knights of Malta

- Mithraism

- Monumental Complex of S. Spirito in Sassia

- Ponte Sisto

- Porta Pia

- 'Protestant' Cemetery

- Quartiere Coppedè

- Scala Santa

- Spanish Steps

- 'Talking' Statues

- Tiber Island

- Villa Borghese

- Vittoriano

- Rioni

- On This Day in Italy

-

Pictures from Italy

-

Florence

>

- A Literary Tour

- Anna Maria Luisa: Last of the Medici

- Casa-Galleria Vichi

- Column of Justice

- Column of St Zenobius

- Cosimo I de' Medici

- Cosimo II de' Medici

- Costanza Bonarelli

- David With Fig Leaf

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning

- Equestrian Statue of Cosimo I de' Medici

- Equestrian Statue of Ferdinando I de' Medici

- Festina Lente

- Floods

- Fontana del Bacchino

- Fontana dei Puttini

- Fountain of Neptune

- Fountains of the Marine Monsters

- Gian Gastone de' Medici

- Girolamo Savonarola

- Images of the Annunciation

- Little Devil

- Monument to Cellini

- Palazzo Bartolini-Salimbeni

- Palazzo Bianca Cappello

- Palazzo Fenzi

- Palazzo Viviani

- Perseus and Medusa

- Piazza Santa Maria Novella

- Pope Leo XI

- Porta della Mandorla

- Rape of the Sabine Woman

- Santa Maria Novella

- Canons' Palace

- Statue of Dante

- Theft of the Century

- Torre del Arnolfo

- Twelve Good Men

- Villa Gamberaia

- Wheel of the Innocents

- 'Wine Windows'

- Lazio >

- Tuscany >

-

Venice

>

- Ab Urbe Condita

- Acqua Alta

- Bartolomeo Colleoni

- Barque of Dante

- Burano

- Caffè Florian

- Daniele Manin

- Flagpoles

- Giustina Rossi

- Gondolas

- Harry's Bar

- Henry James

- House of Three Eyes

- King Victor Emmanuel II

- Map of Venice

- Martinmas

- Master of the House

- Palazzo Contarini Fasan

- Ponte Borgoloco

- Ponte Chiodo

- Punta del Dogana

- Scacciadiavoli

- Shrine of St Lucia

- Sior Antonio Rioba

- The 'Book Shitter'

- The Lion's Mouth

- Tommaso Rangone

- Torcello

- Venus

- 'Viennese Oranges'

- Wellheads

- Winged Lions

-

Florence

>

- Popes: 1417-Present

- Cloisters

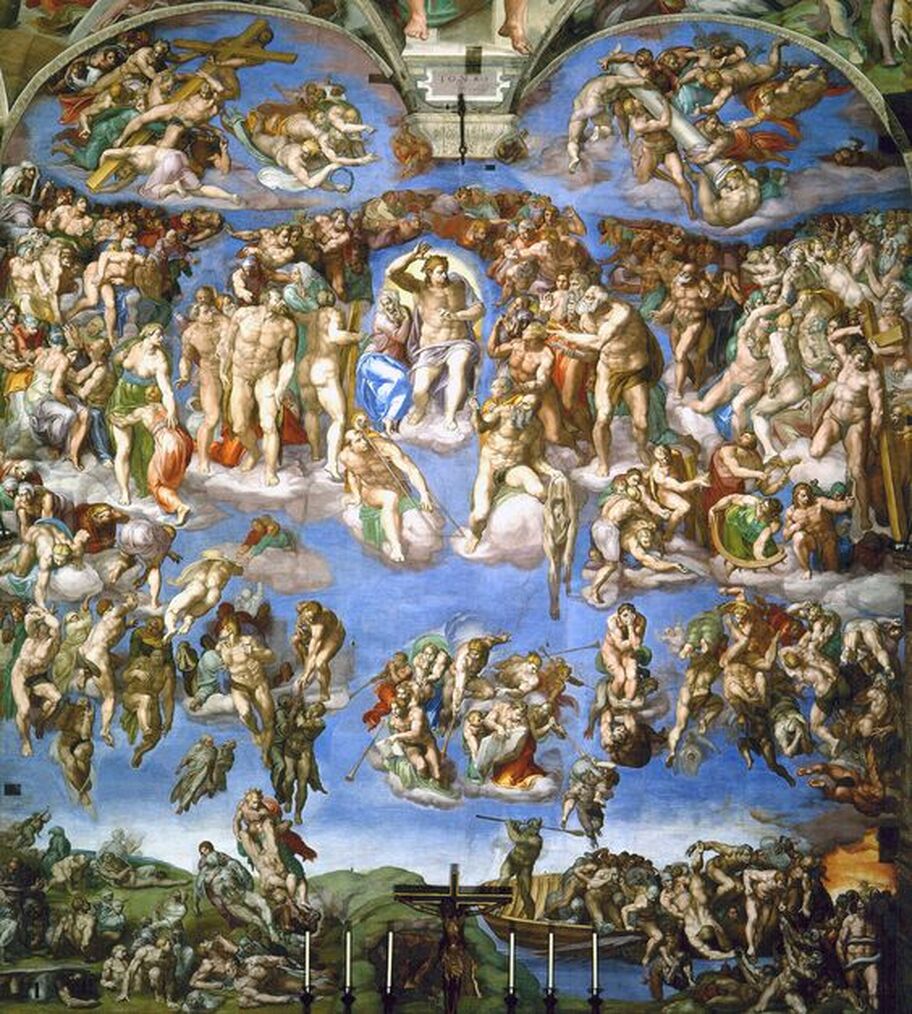

The Sistine Chapel

The Last Judgement

In 1534, more than twenty years after he had finished painting the ceiling, Michelangelo was persuaded by Pope Clement VII (r. 1523-34), a fellow citizen of Florence, to return to the Sistine Chapel to repaint its west wall with an image of the Resurrection. However, on September 25th of the same year the pope died. Clement’s successor, Pope Paul III (r. 1534-49), was just as keen to secure the services of the greatest artist in the world and repeated his predecessor’s offer of a commission. Michelangelo could hardly refuse a request from one pope, having accepted that of another. However, Paul III wanted the west wall of the chapel to be painted with an image of the Last Judgement rather than the Resurrection.

In order to prepare the wall for the fresco, Michelangelo had to destroy both his own work and that of fellow artist, Pietro Perugino. In addition, the two windows were filled in to create a surface 13.7 metres by 12.2 metres, for what would be, at the time, the largest single fresco in the world. In 1536, more than twenty years after he had finished painted the ceiling, he began work on the west wall. By this time, Michelangelo had turned sixty and the challenge facing him was one which would have proved daunting to a man half his age! Five years later, on October 31st 1541, the Last Judgement was unveiled to the public.

In order to prepare the wall for the fresco, Michelangelo had to destroy both his own work and that of fellow artist, Pietro Perugino. In addition, the two windows were filled in to create a surface 13.7 metres by 12.2 metres, for what would be, at the time, the largest single fresco in the world. In 1536, more than twenty years after he had finished painted the ceiling, he began work on the west wall. By this time, Michelangelo had turned sixty and the challenge facing him was one which would have proved daunting to a man half his age! Five years later, on October 31st 1541, the Last Judgement was unveiled to the public.

“When the Son of Man shall come in His glory and all the holy angels with Him, then shall He sit upon the throne of His glory. And before Him shall be gathered all nations, and He shall separate them one from another as a shepherd divideth his sheep from the goats. And He shall set the sheep on His right hand, but the goats on the left” (Matthew 26:31-33).

In his visualisation of the Last Judgement, Michelangelo broke away from the traditional format, which divided the pictorial space horizontally, with heaven above and hell below. Instead, he divided the fresco into two vertical zones, with the figure of Christ the Judge, his right arm raised rather imperiously, dominating the centre of the composition. The Virgin Mary, to his right, turns away from her son with a look of resignation. She can no longer intercede on behalf of mankind, but must await the result of the final judgement. In the centre of the lower section, the angels of the Apocalypse blow their trumpets to waken the dead and announce the end of time. Christ signals his judgement through the movement of his hands, raising his right hand to lift the blessed to heaven, while turning his left hand downwards to send the damned on their final journey to hell.

In his visualisation of the Last Judgement, Michelangelo broke away from the traditional format, which divided the pictorial space horizontally, with heaven above and hell below. Instead, he divided the fresco into two vertical zones, with the figure of Christ the Judge, his right arm raised rather imperiously, dominating the centre of the composition. The Virgin Mary, to his right, turns away from her son with a look of resignation. She can no longer intercede on behalf of mankind, but must await the result of the final judgement. In the centre of the lower section, the angels of the Apocalypse blow their trumpets to waken the dead and announce the end of time. Christ signals his judgement through the movement of his hands, raising his right hand to lift the blessed to heaven, while turning his left hand downwards to send the damned on their final journey to hell.

Surrounding Christ and the Madonna are a number of saints. The two most prominent are St Lawrence and St Bartholomew, whom we see below Christ’s feet. St Bartholomew holds a knife in his right hand and his flayed skin in his left. The face of the latter bears the features of Michelangelo. The two saints enjoy such a privileged position, because their feast-days were linked, respectively, to the coronation of Pope Sixtus IV and the anniversary of the chapel’s foundation.

At the edge of this central group, and to the left, are female saints, martyrs and heroines from the Old Testament, while to the right are the equivalent male figures.

At the edge of this central group, and to the left, are female saints, martyrs and heroines from the Old Testament, while to the right are the equivalent male figures.

In the upper section of the fresco we see groups of angels bearing the instruments of Christ’s Passion (the cross, the crown of thorns, the column), symbols of his sacrifice and the redemption of humanity.

At the bottom of the fresco we see Charon shipping the damned to Minos, the infernal judge, whose body is wrapped in the coils of a snake. This is a clear reference to Dante’s Divina Commedia.

Biagio da Cesena, who was the chapel’s Master of Ceremonies during the period Michelangelo was at work there, was very critical of the amount of naked flesh he observed in the fresco. Instead of keeping his opinions to himself, he expressed them very strongly in a letter to the pope: ‘It was most dishonest in such an honoured place to have painted so many nude figures who so dishonestly show their shame and that it was not a work for a Chapel of the Pope but for stewpots and taverns’. These views made their way to Michelangelo, who responded by giving Minos the features of the carping MC. To add insult to injury, Michelangelo depicted the serpent, which coils itself around the body of Minos/Biagio, in the act of biting a rather personal part of his anatomy!

But, perhaps, the Master of Ceremonies had the last laugh, for a few years after the fresco was painted the Catholic Church, in the wake of the reforming zeal of the Council of Trent (1545-63), decided to tighten up its control of images which it deemed inappropriate. The Mannerist painter, Daniele da Volterra, was duly brought in to ‘retouch’ the many nudes in Michelangelo’s fresco. Needless to say, such over-painting was carried out after Michelangelo’s death in 1564. Volterra’s addition of ‘drapery’ to the nude figures led to his being nicknamed Il Braghettone (the Breeches Man). Such censorship continued into the 18th and 19th centuries.

When the fresco of the Last Judgement was being restored (1980-94) a decision had to be made as to whether the over-painting should be removed. It was decided that the later additions should go, but Volterra’s initial retouching should remain, as witness to an important moment in the history of the Catholic Church.

At the bottom of the fresco we see Charon shipping the damned to Minos, the infernal judge, whose body is wrapped in the coils of a snake. This is a clear reference to Dante’s Divina Commedia.

Biagio da Cesena, who was the chapel’s Master of Ceremonies during the period Michelangelo was at work there, was very critical of the amount of naked flesh he observed in the fresco. Instead of keeping his opinions to himself, he expressed them very strongly in a letter to the pope: ‘It was most dishonest in such an honoured place to have painted so many nude figures who so dishonestly show their shame and that it was not a work for a Chapel of the Pope but for stewpots and taverns’. These views made their way to Michelangelo, who responded by giving Minos the features of the carping MC. To add insult to injury, Michelangelo depicted the serpent, which coils itself around the body of Minos/Biagio, in the act of biting a rather personal part of his anatomy!

But, perhaps, the Master of Ceremonies had the last laugh, for a few years after the fresco was painted the Catholic Church, in the wake of the reforming zeal of the Council of Trent (1545-63), decided to tighten up its control of images which it deemed inappropriate. The Mannerist painter, Daniele da Volterra, was duly brought in to ‘retouch’ the many nudes in Michelangelo’s fresco. Needless to say, such over-painting was carried out after Michelangelo’s death in 1564. Volterra’s addition of ‘drapery’ to the nude figures led to his being nicknamed Il Braghettone (the Breeches Man). Such censorship continued into the 18th and 19th centuries.

When the fresco of the Last Judgement was being restored (1980-94) a decision had to be made as to whether the over-painting should be removed. It was decided that the later additions should go, but Volterra’s initial retouching should remain, as witness to an important moment in the history of the Catholic Church.

- Home

- Walking Tours

- Blog

-

St Peter's Basilica

- Altars

- Baldacchino

- Chair of St Peter

- Chapel of the Baptistery

- Chapel of the Bl. Sacrament

- Chapel of the Choir

- Chapel of the Pieta

- Crossing >

- Dome

-

Monuments

>

- Countess Matilda of Canossa

- Maria Clementina Sobieska

- Queen Christina of Sweden

- Pope Innocent VIII

- Pope Paul III

- Pope Gregory XIII

- Pope Gregory XIV

- Pope Leo XI

- Pope Urban VIII

- Pope Alexander VII

- Pope Clement X

- Pope Innocent XI

- Pope Alexander VIII

- Pope Innocent XII

- Pope Benedict XIV

- Pope Clement XIII

- Pope Pius VII

- Pope Leo XII

- Pope Pius VIII

- Pope Gregory XVI

- Pope Pius X

- Pope Benedict XV

- Pope Pius XI

- Pope Pius XII

- Pope John XXIII

- The Stuarts

- Nave

- Portico >

- Statue of St Peter

- Statues of Founder Saints

- Transept

- Tribune

- St Peter's Square

- Vatican Museums

- Sistine Chapel

-

Fountains

- Trevi Fountain

- Fontana della Barcaccia

- Fontana della Peschiera

- Fountain in Piazza Colonna

- Fountain in Piazza delle Cinque Scole

- Fountain in Piazza dell' Aracoeli

- Fountain in Piazza Nicosia

- Fountain in Piazza di S.M. in Trastevere

- Fountain of Moses

- Fountain of Neptune

- Fountains of Piazza Farnese

- Fountain of Ponte Sisto

- Fountain of the Acqua Paola

- Fountain of the Bees

- Fountain of the Cannonball

- Fountain of the Frogs

- Fountain of the Four Rivers

- Fountain of the Goddess Roma

- Fountain of the Lateran Obelisk

- Fountain of the Mask

- Fountain of the Moor

- Fountain of the Naiads

- Fountain of the Pantheon

- Fountains of Piazza del Popolo

- Fountain of the Porter

- Fountains of St Peter's Square

- Fountain of the Seahorses

- Fountain of the Triton

- Fountain of the Turtles

- Fountains of the Two Seas

- Four Fountains

- Rioni Fountains

- Street Fountains

- Venice Marries the Sea

- On This Day in Rome

-

Churches

- Chiesa del Gesù >

- Chiesa Nuova

- Lateran Baptistery

- San Bartolomeo all' Isola

- San Benedetto in Piscinula

- San Bernardo alle Terme

- San Carlo ai Catinari

- San Carlo al Corso

- San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane

- San Clemente >

- San Crisogono

- San Francesco a Ripa >

- San Giorgio in Velabro

- San Giovanni a Porta Latina

- San Giovanni dei Fiorentini

- San Giovanni in Laterano >

- San Girolamo della Carità >

- San Gregorio Magno

- San Lorenzo fuori le Mura

- San Lorenzo in Damaso

- San Lorenzo in Lucina

- San Luigi dei Francesi >

- San Marcello al Corso

- San Marco

- San Martino ai Monti

- San Nicola in Carcere

- San Pancrazio

- San Paolo fuori le Mura

- San Pietro in Montorio

- San Pietro in Vincoli

- San Saba

- San Salvatore in Lauro

- San Sebastiano fuori le Mura >

- San Silvestro in Capite

- San Vitale

- Sant' Agnese fuori le Mura

- Sant' Agnese in Agone

- Sant' Agostino

- Sant' Alessio

- Sant' Anastasia

- Sant' Andrea al Quirinale

- Sant' Andrea della Valle

- Sant' Andrea delle Fratte

- Sant' Antonio dei Portoghesi

- Sant' Apollinare

- Sant' Eustachio

- Sant' Ignazio di Loyola

- Sant' Ivo alla Sapienza

- Santa Caterina dei Funari

- Santa Cecilia in Trastevere

- Santa Costanza

- Santa Croce in Gerusalemme >

- Santa Francesca Romana

- Santa Maria ad Martyres

- Santa Maria degli Angeli

- Santa Maria dei Miracoli

- Santa Maria del Popolo >

- Santa Maria del Priorato

- Santa Maria della Pace >

- Santa Maria della Vittoria >

- Santa Maria dell' Anima

- Santa Maria dell' Orazione e Morte

- Santa Maria dell' Orto

- Santa Maria di Loreto

- Santa Maria in Aracoeli >

- Santa Maria in Campitelli

- Santa Maria in Cosmedin

- Santa Maria in Domnica

- Santa Maria in Montesanto

- Santa Maria in Trastevere >

- Santa Maria in Via

- Santa Maria in Via Lata

- Santa Maria Maddalena

- Santa Maria Maggiore >

- Santa Maria sopra Minerva >

- Santa Prassede

- Santa Pudenziana

- Santa Sabina >

- Santa Susanna

- Santi Apostoli

- Santi Cosma e Damiano

- Santi Domenico e Sisto

- Santi Giovanni e Paolo

- Santi Luca e Martina

- Santi Nereo e Achilleo

- Santi Quattro Coronati

- Santi Vincenzo e Anastasio

- Santissima Trinità degli Spagnoli

- Santissima Trinità dei Pellegrini

- Santissima Trinità di Monti

- Santissimo Nome di Maria

- Santo Stefano Rotondo

- Palatine

- Forum

-

Ancient Monuments

- Aqueducts

- Ara Pacis

- Arch of Constantine

- Arch of the Money-Changers

- Arch of Janus

- Aurelian Walls

- Baths of Caracalla

- Baths of Diocletian

- Castel Sant' Angelo

- Catacombs of Domitilla

- Circus Maxentius

- Circus Maximus

- Colosseum

- Column of Marcus Aurelius

- Column of Trajan

- Forum of Augustus

- Forum of Trajan

- Mausoleum of Augustus

- Nymphaeum

- Pantheon

- Ponte Fabricio

- Ponte Milvio

- Ponte Rotto

- Ponte Sant' Angelo

- Porta Maggiore

- Porta San Paolo

- Porta San Sebastiano

- Portico of Octavia

- Pyramid of Cestius

- Temple of Hadrian

- Temple of Hercules

- Temple of Portunus

- Theatre of Balbus

- Theatre of Marcellus

- Theatre of Pompey

- Tomb of Caecilia Metella

- Via Appia

-

Obelisks

- 'Minerveo' Obelisk

- 'Flaminio' Obelisk

- 'Matteiano' Obelisk

- 'Lateran' Obelisk

- 'Dogali' Obelisk

- 'Macuteo' Obelisk

- 'Solare' Obelisk

- 'Vatican' Obelisk

- 'Agonalis' Obelisk

- 'Sallustiano' Obelisk

- 'Quirinale' Obelisk

- 'Esquiline' Obelisk

- 'Pinciano' Obelisk

- 'Mediceo' Obelisk

- 'Torlonia' Obelisks

- 'Mussolini' Obelisk

- 'Marconi' Obelisk

-

Mosaics

- Gallery

- Palazzi

- Galleries & Museums

- Piazzas

-

Miscellaneous

- A Calendar of Saints

- A Literary Tour

- Antico Caffè Greco

- Art of the Cosmati

- Babington's Tea Rooms

- Barberini Bees

- Gian Lorenzo Bernini

- Borromini & the Baroque

- Catacombs

- Column of the Immaculate Conception

- Domes

- Equestrian Statues

- EUR

- Fasces

- Flood Plaques

- Funerary Monuments

- House of the Owls

- Jewish Ghetto

- Jubilee Years

- Knights of Malta

- Mithraism

- Monumental Complex of S. Spirito in Sassia

- Ponte Sisto

- Porta Pia

- 'Protestant' Cemetery

- Quartiere Coppedè

- Scala Santa

- Spanish Steps

- 'Talking' Statues

- Tiber Island

- Villa Borghese

- Vittoriano

- Rioni

- On This Day in Italy

-

Pictures from Italy

-

Florence

>

- A Literary Tour

- Anna Maria Luisa: Last of the Medici

- Casa-Galleria Vichi

- Column of Justice

- Column of St Zenobius

- Cosimo I de' Medici

- Cosimo II de' Medici

- Costanza Bonarelli

- David With Fig Leaf

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning

- Equestrian Statue of Cosimo I de' Medici

- Equestrian Statue of Ferdinando I de' Medici

- Festina Lente

- Floods

- Fontana del Bacchino

- Fontana dei Puttini

- Fountain of Neptune

- Fountains of the Marine Monsters

- Gian Gastone de' Medici

- Girolamo Savonarola

- Images of the Annunciation

- Little Devil

- Monument to Cellini

- Palazzo Bartolini-Salimbeni

- Palazzo Bianca Cappello

- Palazzo Fenzi

- Palazzo Viviani

- Perseus and Medusa

- Piazza Santa Maria Novella

- Pope Leo XI

- Porta della Mandorla

- Rape of the Sabine Woman

- Santa Maria Novella

- Canons' Palace

- Statue of Dante

- Theft of the Century

- Torre del Arnolfo

- Twelve Good Men

- Villa Gamberaia

- Wheel of the Innocents

- 'Wine Windows'

- Lazio >

- Tuscany >

-

Venice

>

- Ab Urbe Condita

- Acqua Alta

- Bartolomeo Colleoni

- Barque of Dante

- Burano

- Caffè Florian

- Daniele Manin

- Flagpoles

- Giustina Rossi

- Gondolas

- Harry's Bar

- Henry James

- House of Three Eyes

- King Victor Emmanuel II

- Map of Venice

- Martinmas

- Master of the House

- Palazzo Contarini Fasan

- Ponte Borgoloco

- Ponte Chiodo

- Punta del Dogana

- Scacciadiavoli

- Shrine of St Lucia

- Sior Antonio Rioba

- The 'Book Shitter'

- The Lion's Mouth

- Tommaso Rangone

- Torcello

- Venus

- 'Viennese Oranges'

- Wellheads

- Winged Lions

-

Florence

>

- Popes: 1417-Present

- Cloisters