- Home

- Walking Tours

- Blog

-

St Peter's Basilica

- Altars

- Baldacchino

- Chair of St Peter

- Chapel of the Baptistery

- Chapel of the Bl. Sacrament

- Chapel of the Choir

- Chapel of the Pieta

- Crossing >

- Dome

-

Monuments

>

- Countess Matilda of Canossa

- Maria Clementina Sobieska

- Queen Christina of Sweden

- Pope Innocent VIII

- Pope Paul III

- Pope Gregory XIII

- Pope Gregory XIV

- Pope Leo XI

- Pope Urban VIII

- Pope Alexander VII

- Pope Clement X

- Pope Innocent XI

- Pope Alexander VIII

- Pope Innocent XII

- Pope Benedict XIV

- Pope Clement XIII

- Pope Pius VII

- Pope Leo XII

- Pope Pius VIII

- Pope Gregory XVI

- Pope Pius X

- Pope Benedict XV

- Pope Pius XI

- Pope Pius XII

- Pope John XXIII

- The Stuarts

- Nave

- Portico >

- Statue of St Peter

- Statues of Founder Saints

- Transept

- Tribune

- St Peter's Square

- Vatican Museums

- Sistine Chapel

-

Fountains

- Trevi Fountain

- Fontana della Barcaccia

- Fontana della Peschiera

- Fountain in Piazza Colonna

- Fountain in Piazza delle Cinque Scole

- Fountain in Piazza dell' Aracoeli

- Fountain in Piazza Nicosia

- Fountain in Piazza di S.M. in Trastevere

- Fountain of Moses

- Fountain of Neptune

- Fountains of Piazza Farnese

- Fountain of Ponte Sisto

- Fountain of the Acqua Paola

- Fountain of the Bees

- Fountain of the Cannonball

- Fountain of the Frogs

- Fountain of the Four Rivers

- Fountain of the Goddess Roma

- Fountain of the Lateran Obelisk

- Fountain of the Mask

- Fountain of the Moor

- Fountain of the Naiads

- Fountain of the Pantheon

- Fountains of Piazza del Popolo

- Fountain of the Porter

- Fountains of St Peter's Square

- Fountain of the Seahorses

- Fountain of the Triton

- Fountain of the Turtles

- Fountains of the Two Seas

- Four Fountains

- Rioni Fountains

- Street Fountains

- Venice Marries the Sea

- On This Day in Rome

-

Churches

- Chiesa del Gesù >

- Chiesa Nuova

- Lateran Baptistery

- San Bartolomeo all' Isola

- San Benedetto in Piscinula

- San Bernardo alle Terme

- San Carlo ai Catinari

- San Carlo al Corso

- San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane

- San Clemente >

- San Crisogono

- San Francesco a Ripa >

- San Giorgio in Velabro

- San Giovanni a Porta Latina

- San Giovanni dei Fiorentini

- San Giovanni in Laterano >

- San Girolamo della Carità >

- San Gregorio Magno

- San Lorenzo fuori le Mura

- San Lorenzo in Damaso

- San Lorenzo in Lucina

- San Luigi dei Francesi >

- San Marcello al Corso

- San Marco

- San Martino ai Monti

- San Nicola in Carcere

- San Pancrazio

- San Paolo fuori le Mura

- San Pietro in Montorio

- San Pietro in Vincoli

- San Saba

- San Salvatore in Lauro

- San Sebastiano fuori le Mura >

- San Silvestro in Capite

- San Vitale

- Sant' Agnese fuori le Mura

- Sant' Agnese in Agone

- Sant' Agostino

- Sant' Alessio

- Sant' Anastasia

- Sant' Andrea al Quirinale

- Sant' Andrea della Valle

- Sant' Andrea delle Fratte

- Sant' Antonio dei Portoghesi

- Sant' Apollinare

- Sant' Eustachio

- Sant' Ignazio di Loyola

- Sant' Ivo alla Sapienza

- Santa Caterina dei Funari

- Santa Cecilia in Trastevere

- Santa Costanza

- Santa Croce in Gerusalemme >

- Santa Francesca Romana

- Santa Maria ad Martyres

- Santa Maria degli Angeli

- Santa Maria dei Miracoli

- Santa Maria del Popolo >

- Santa Maria del Priorato

- Santa Maria della Pace >

- Santa Maria della Vittoria >

- Santa Maria dell' Anima

- Santa Maria dell' Orazione e Morte

- Santa Maria dell' Orto

- Santa Maria di Loreto

- Santa Maria in Aracoeli >

- Santa Maria in Campitelli

- Santa Maria in Cosmedin

- Santa Maria in Domnica

- Santa Maria in Montesanto

- Santa Maria in Trastevere >

- Santa Maria in Via

- Santa Maria in Via Lata

- Santa Maria Maddalena

- Santa Maria Maggiore >

- Santa Maria sopra Minerva >

- Santa Prassede

- Santa Pudenziana

- Santa Sabina >

- Santa Susanna

- Santi Apostoli

- Santi Cosma e Damiano

- Santi Domenico e Sisto

- Santi Giovanni e Paolo

- Santi Luca e Martina

- Santi Nereo e Achilleo

- Santi Quattro Coronati

- Santi Vincenzo e Anastasio

- Santissima Trinità degli Spagnoli

- Santissima Trinità dei Pellegrini

- Santissima Trinità di Monti

- Santissimo Nome di Maria

- Santo Stefano Rotondo

- Palatine

- Forum

-

Ancient Monuments

- Aqueducts

- Ara Pacis

- Arch of Constantine

- Arch of the Money-Changers

- Arch of Janus

- Aurelian Walls

- Baths of Caracalla

- Baths of Diocletian

- Castel Sant' Angelo

- Catacombs of Domitilla

- Circus Maxentius

- Circus Maximus

- Colosseum

- Column of Marcus Aurelius

- Column of Trajan

- Forum of Augustus

- Forum of Trajan

- Mausoleum of Augustus

- Nymphaeum

- Pantheon

- Ponte Fabricio

- Ponte Milvio

- Ponte Rotto

- Ponte Sant' Angelo

- Porta Maggiore

- Porta San Paolo

- Porta San Sebastiano

- Portico of Octavia

- Pyramid of Cestius

- Temple of Hadrian

- Temple of Hercules

- Temple of Portunus

- Theatre of Balbus

- Theatre of Marcellus

- Theatre of Pompey

- Tomb of Caecilia Metella

- Via Appia

-

Obelisks

- 'Minerveo' Obelisk

- 'Flaminio' Obelisk

- 'Matteiano' Obelisk

- 'Lateran' Obelisk

- 'Dogali' Obelisk

- 'Macuteo' Obelisk

- 'Solare' Obelisk

- 'Vatican' Obelisk

- 'Agonalis' Obelisk

- 'Sallustiano' Obelisk

- 'Quirinale' Obelisk

- 'Esquiline' Obelisk

- 'Pinciano' Obelisk

- 'Mediceo' Obelisk

- 'Torlonia' Obelisks

- 'Mussolini' Obelisk

- 'Marconi' Obelisk

-

Mosaics

- Gallery

- Palazzi

- Galleries & Museums

- Piazzas

-

Miscellaneous

- A Calendar of Saints

- A Literary Tour

- Antico Caffè Greco

- Art of the Cosmati

- Babington's Tea Rooms

- Barberini Bees

- Gian Lorenzo Bernini

- Borromini & the Baroque

- Catacombs

- Column of the Immaculate Conception

- Domes

- Equestrian Statues

- EUR

- Fasces

- Flood Plaques

- Funerary Monuments

- House of the Owls

- Jewish Ghetto

- Jubilee Years

- Knights of Malta

- Mithraism

- Monumental Complex of S. Spirito in Sassia

- Ponte Sisto

- Porta Pia

- 'Protestant' Cemetery

- Quartiere Coppedè

- Scala Santa

- Spanish Steps

- 'Talking' Statues

- Tiber Island

- Villa Borghese

- Vittoriano

- Rioni

- On This Day in Italy

-

Pictures from Italy

-

Florence

>

- A Literary Tour

- Anna Maria Luisa: Last of the Medici

- Casa-Galleria Vichi

- Column of Justice

- Column of St Zenobius

- Cosimo I de' Medici

- Cosimo II de' Medici

- Costanza Bonarelli

- David With Fig Leaf

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning

- Equestrian Statue of Cosimo I de' Medici

- Equestrian Statue of Ferdinando I de' Medici

- Festina Lente

- Floods

- Fontana del Bacchino

- Fontana dei Puttini

- Fountain of Neptune

- Fountains of the Marine Monsters

- Gian Gastone de' Medici

- Girolamo Savonarola

- Images of the Annunciation

- Little Devil

- Monument to Cellini

- Palazzo Bartolini-Salimbeni

- Palazzo Bianca Cappello

- Palazzo Fenzi

- Palazzo Viviani

- Perseus and Medusa

- Piazza Santa Maria Novella

- Pope Leo XI

- Porta della Mandorla

- Rape of the Sabine Woman

- Santa Maria Novella

- Canons' Palace

- Statue of Dante

- Theft of the Century

- Torre del Arnolfo

- Twelve Good Men

- Villa Gamberaia

- Wheel of the Innocents

- 'Wine Windows'

- Lazio >

- Tuscany >

-

Venice

>

- Ab Urbe Condita

- Acqua Alta

- Bartolomeo Colleoni

- Barque of Dante

- Burano

- Caffè Florian

- Daniele Manin

- Flagpoles

- Giustina Rossi

- Gondolas

- Harry's Bar

- Henry James

- House of Three Eyes

- King Victor Emmanuel II

- Map of Venice

- Martinmas

- Master of the House

- Palazzo Contarini Fasan

- Ponte Borgoloco

- Ponte Chiodo

- Punta del Dogana

- Scacciadiavoli

- Shrine of St Lucia

- Sior Antonio Rioba

- The 'Book Shitter'

- The Lion's Mouth

- Tommaso Rangone

- Torcello

- Venus

- 'Viennese Oranges'

- Wellheads

- Winged Lions

-

Florence

>

- Popes: 1417-Present

- Cloisters

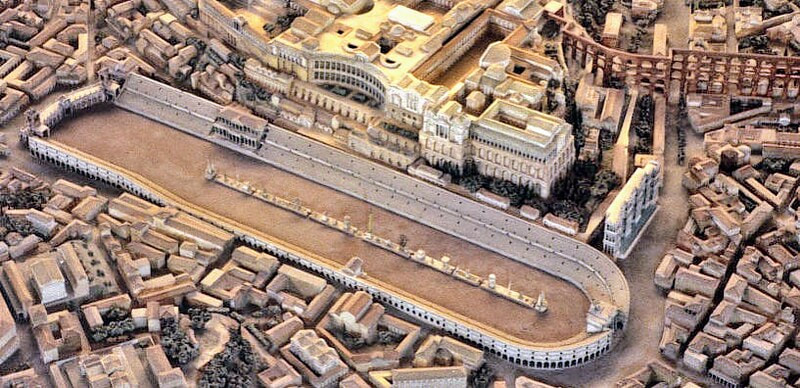

Circus Maximus

Almost nothing above ground remains of what was once Rome's oldest and largest stadium. Occupying the whole length of a valley between the Palatine and Aventine hills, the Circus Maximus dates back to the 6th century BCE.

The Circus Maximus was a racetrack for chariots and home to the Roman Games (Ludi Romani), an ancient festival of races and military displays, which was held annually for 15 days in September.

In its fully developed form, in the 1st century CE, the stadium was 540 metres long and 80 metres wide. The banks of seating were 30 metres deep and 28 metres high and may have held as many as 250,000 spectators.

There were 12 starting gates, arranged in an arc at one end of the track, and the chariots, which were driven by two or more horses, had to complete seven laps of the circuit, racing anti-clockwise. The laps were first recorded by large wooden eggs and later by bronze dolphins.

The chariot-drivers were all members of one of four teams: the whites, the blues, the reds, and the greens, each with its own following of fanatics. The races were held throughout the day and were the most popular pastime in the city. Before the races started the spectators were treated to a variety of skilful equestrian displays.

The remains of the central track or spina, around which the chariots raced, lies about 9 m underground. The two obelisks which now stand respectively in Piazza del Popolo and Piazza San Giovanni in Laterano, were dug up here in 1587. The obelisks would originally have stood on the spina, in the centre of the track.

The Circus Maximus remained in regular use until the middle of the 6th century. During the middle-ages the site reverted to fields and by the 19th century it was covered by various industrial enterprises, including the city’s gasworks. The whole area was cleared in the 1930s when it became a designated park.

The Circus Maximus was a racetrack for chariots and home to the Roman Games (Ludi Romani), an ancient festival of races and military displays, which was held annually for 15 days in September.

In its fully developed form, in the 1st century CE, the stadium was 540 metres long and 80 metres wide. The banks of seating were 30 metres deep and 28 metres high and may have held as many as 250,000 spectators.

There were 12 starting gates, arranged in an arc at one end of the track, and the chariots, which were driven by two or more horses, had to complete seven laps of the circuit, racing anti-clockwise. The laps were first recorded by large wooden eggs and later by bronze dolphins.

The chariot-drivers were all members of one of four teams: the whites, the blues, the reds, and the greens, each with its own following of fanatics. The races were held throughout the day and were the most popular pastime in the city. Before the races started the spectators were treated to a variety of skilful equestrian displays.

The remains of the central track or spina, around which the chariots raced, lies about 9 m underground. The two obelisks which now stand respectively in Piazza del Popolo and Piazza San Giovanni in Laterano, were dug up here in 1587. The obelisks would originally have stood on the spina, in the centre of the track.

The Circus Maximus remained in regular use until the middle of the 6th century. During the middle-ages the site reverted to fields and by the 19th century it was covered by various industrial enterprises, including the city’s gasworks. The whole area was cleared in the 1930s when it became a designated park.

- Home

- Walking Tours

- Blog

-

St Peter's Basilica

- Altars

- Baldacchino

- Chair of St Peter

- Chapel of the Baptistery

- Chapel of the Bl. Sacrament

- Chapel of the Choir

- Chapel of the Pieta

- Crossing >

- Dome

-

Monuments

>

- Countess Matilda of Canossa

- Maria Clementina Sobieska

- Queen Christina of Sweden

- Pope Innocent VIII

- Pope Paul III

- Pope Gregory XIII

- Pope Gregory XIV

- Pope Leo XI

- Pope Urban VIII

- Pope Alexander VII

- Pope Clement X

- Pope Innocent XI

- Pope Alexander VIII

- Pope Innocent XII

- Pope Benedict XIV

- Pope Clement XIII

- Pope Pius VII

- Pope Leo XII

- Pope Pius VIII

- Pope Gregory XVI

- Pope Pius X

- Pope Benedict XV

- Pope Pius XI

- Pope Pius XII

- Pope John XXIII

- The Stuarts

- Nave

- Portico >

- Statue of St Peter

- Statues of Founder Saints

- Transept

- Tribune

- St Peter's Square

- Vatican Museums

- Sistine Chapel

-

Fountains

- Trevi Fountain

- Fontana della Barcaccia

- Fontana della Peschiera

- Fountain in Piazza Colonna

- Fountain in Piazza delle Cinque Scole

- Fountain in Piazza dell' Aracoeli

- Fountain in Piazza Nicosia

- Fountain in Piazza di S.M. in Trastevere

- Fountain of Moses

- Fountain of Neptune

- Fountains of Piazza Farnese

- Fountain of Ponte Sisto

- Fountain of the Acqua Paola

- Fountain of the Bees

- Fountain of the Cannonball

- Fountain of the Frogs

- Fountain of the Four Rivers

- Fountain of the Goddess Roma

- Fountain of the Lateran Obelisk

- Fountain of the Mask

- Fountain of the Moor

- Fountain of the Naiads

- Fountain of the Pantheon

- Fountains of Piazza del Popolo

- Fountain of the Porter

- Fountains of St Peter's Square

- Fountain of the Seahorses

- Fountain of the Triton

- Fountain of the Turtles

- Fountains of the Two Seas

- Four Fountains

- Rioni Fountains

- Street Fountains

- Venice Marries the Sea

- On This Day in Rome

-

Churches

- Chiesa del Gesù >

- Chiesa Nuova

- Lateran Baptistery

- San Bartolomeo all' Isola

- San Benedetto in Piscinula

- San Bernardo alle Terme

- San Carlo ai Catinari

- San Carlo al Corso

- San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane

- San Clemente >

- San Crisogono

- San Francesco a Ripa >

- San Giorgio in Velabro

- San Giovanni a Porta Latina

- San Giovanni dei Fiorentini

- San Giovanni in Laterano >

- San Girolamo della Carità >

- San Gregorio Magno

- San Lorenzo fuori le Mura

- San Lorenzo in Damaso

- San Lorenzo in Lucina

- San Luigi dei Francesi >

- San Marcello al Corso

- San Marco

- San Martino ai Monti

- San Nicola in Carcere

- San Pancrazio

- San Paolo fuori le Mura

- San Pietro in Montorio

- San Pietro in Vincoli

- San Saba

- San Salvatore in Lauro

- San Sebastiano fuori le Mura >

- San Silvestro in Capite

- San Vitale

- Sant' Agnese fuori le Mura

- Sant' Agnese in Agone

- Sant' Agostino

- Sant' Alessio

- Sant' Anastasia

- Sant' Andrea al Quirinale

- Sant' Andrea della Valle

- Sant' Andrea delle Fratte

- Sant' Antonio dei Portoghesi

- Sant' Apollinare

- Sant' Eustachio

- Sant' Ignazio di Loyola

- Sant' Ivo alla Sapienza

- Santa Caterina dei Funari

- Santa Cecilia in Trastevere

- Santa Costanza

- Santa Croce in Gerusalemme >

- Santa Francesca Romana

- Santa Maria ad Martyres

- Santa Maria degli Angeli

- Santa Maria dei Miracoli

- Santa Maria del Popolo >

- Santa Maria del Priorato

- Santa Maria della Pace >

- Santa Maria della Vittoria >

- Santa Maria dell' Anima

- Santa Maria dell' Orazione e Morte

- Santa Maria dell' Orto

- Santa Maria di Loreto

- Santa Maria in Aracoeli >

- Santa Maria in Campitelli

- Santa Maria in Cosmedin

- Santa Maria in Domnica

- Santa Maria in Montesanto

- Santa Maria in Trastevere >

- Santa Maria in Via

- Santa Maria in Via Lata

- Santa Maria Maddalena

- Santa Maria Maggiore >

- Santa Maria sopra Minerva >

- Santa Prassede

- Santa Pudenziana

- Santa Sabina >

- Santa Susanna

- Santi Apostoli

- Santi Cosma e Damiano

- Santi Domenico e Sisto

- Santi Giovanni e Paolo

- Santi Luca e Martina

- Santi Nereo e Achilleo

- Santi Quattro Coronati

- Santi Vincenzo e Anastasio

- Santissima Trinità degli Spagnoli

- Santissima Trinità dei Pellegrini

- Santissima Trinità di Monti

- Santissimo Nome di Maria

- Santo Stefano Rotondo

- Palatine

- Forum

-

Ancient Monuments

- Aqueducts

- Ara Pacis

- Arch of Constantine

- Arch of the Money-Changers

- Arch of Janus

- Aurelian Walls

- Baths of Caracalla

- Baths of Diocletian

- Castel Sant' Angelo

- Catacombs of Domitilla

- Circus Maxentius

- Circus Maximus

- Colosseum

- Column of Marcus Aurelius

- Column of Trajan

- Forum of Augustus

- Forum of Trajan

- Mausoleum of Augustus

- Nymphaeum

- Pantheon

- Ponte Fabricio

- Ponte Milvio

- Ponte Rotto

- Ponte Sant' Angelo

- Porta Maggiore

- Porta San Paolo

- Porta San Sebastiano

- Portico of Octavia

- Pyramid of Cestius

- Temple of Hadrian

- Temple of Hercules

- Temple of Portunus

- Theatre of Balbus

- Theatre of Marcellus

- Theatre of Pompey

- Tomb of Caecilia Metella

- Via Appia

-

Obelisks

- 'Minerveo' Obelisk

- 'Flaminio' Obelisk

- 'Matteiano' Obelisk

- 'Lateran' Obelisk

- 'Dogali' Obelisk

- 'Macuteo' Obelisk

- 'Solare' Obelisk

- 'Vatican' Obelisk

- 'Agonalis' Obelisk

- 'Sallustiano' Obelisk

- 'Quirinale' Obelisk

- 'Esquiline' Obelisk

- 'Pinciano' Obelisk

- 'Mediceo' Obelisk

- 'Torlonia' Obelisks

- 'Mussolini' Obelisk

- 'Marconi' Obelisk

-

Mosaics

- Gallery

- Palazzi

- Galleries & Museums

- Piazzas

-

Miscellaneous

- A Calendar of Saints

- A Literary Tour

- Antico Caffè Greco

- Art of the Cosmati

- Babington's Tea Rooms

- Barberini Bees

- Gian Lorenzo Bernini

- Borromini & the Baroque

- Catacombs

- Column of the Immaculate Conception

- Domes

- Equestrian Statues

- EUR

- Fasces

- Flood Plaques

- Funerary Monuments

- House of the Owls

- Jewish Ghetto

- Jubilee Years

- Knights of Malta

- Mithraism

- Monumental Complex of S. Spirito in Sassia

- Ponte Sisto

- Porta Pia

- 'Protestant' Cemetery

- Quartiere Coppedè

- Scala Santa

- Spanish Steps

- 'Talking' Statues

- Tiber Island

- Villa Borghese

- Vittoriano

- Rioni

- On This Day in Italy

-

Pictures from Italy

-

Florence

>

- A Literary Tour

- Anna Maria Luisa: Last of the Medici

- Casa-Galleria Vichi

- Column of Justice

- Column of St Zenobius

- Cosimo I de' Medici

- Cosimo II de' Medici

- Costanza Bonarelli

- David With Fig Leaf

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning

- Equestrian Statue of Cosimo I de' Medici

- Equestrian Statue of Ferdinando I de' Medici

- Festina Lente

- Floods

- Fontana del Bacchino

- Fontana dei Puttini

- Fountain of Neptune

- Fountains of the Marine Monsters

- Gian Gastone de' Medici

- Girolamo Savonarola

- Images of the Annunciation

- Little Devil

- Monument to Cellini

- Palazzo Bartolini-Salimbeni

- Palazzo Bianca Cappello

- Palazzo Fenzi

- Palazzo Viviani

- Perseus and Medusa

- Piazza Santa Maria Novella

- Pope Leo XI

- Porta della Mandorla

- Rape of the Sabine Woman

- Santa Maria Novella

- Canons' Palace

- Statue of Dante

- Theft of the Century

- Torre del Arnolfo

- Twelve Good Men

- Villa Gamberaia

- Wheel of the Innocents

- 'Wine Windows'

- Lazio >

- Tuscany >

-

Venice

>

- Ab Urbe Condita

- Acqua Alta

- Bartolomeo Colleoni

- Barque of Dante

- Burano

- Caffè Florian

- Daniele Manin

- Flagpoles

- Giustina Rossi

- Gondolas

- Harry's Bar

- Henry James

- House of Three Eyes

- King Victor Emmanuel II

- Map of Venice

- Martinmas

- Master of the House

- Palazzo Contarini Fasan

- Ponte Borgoloco

- Ponte Chiodo

- Punta del Dogana

- Scacciadiavoli

- Shrine of St Lucia

- Sior Antonio Rioba

- The 'Book Shitter'

- The Lion's Mouth

- Tommaso Rangone

- Torcello

- Venus

- 'Viennese Oranges'

- Wellheads

- Winged Lions

-

Florence

>

- Popes: 1417-Present

- Cloisters