The Winged Lions of Venice

|

Venice is awash with images of the winged lion of Saint Mark, the symbol of the city's patron saint.

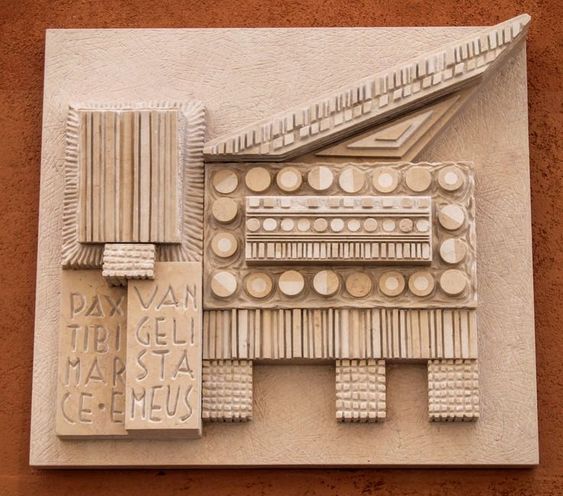

The Venetians transformed the winged lion (leone alato) into their very own Leone Marciano by the addition of a book, which, more often than not, is open to reveal the words: PAX TIBI MARCE EVANGELISTA MEUS (Peace be with you Mark my Evangelist). The origin of the phrase derives from a legend in which Saint Mark was shipwrecked in the Venetian lagoon. An angel appeared to him and declared 'Pax tibi Marce, evangelista meus. Hic requiescet corpus tuum.' The second sentence (which never finds its way onto the lion's page) is the most significant, 'Here your body will rest'. And in 828 the angel's prophecy was fulfilled when two Venetian merchants stole what was believed to be the saint's body from a church in Alexandria. Images of the Leone Marciano took one of two forms: 'andante' and 'in moleca' (or 'in moeca'). He is andante when depicted standing, wings stretched, with one paw resting on an open book. He is in moleca when depicted full-faced, paw on book, wings framing his head. On May 29th 1797, only seventeen days after a young French general by the name of Napoleon Bonaparte had brought to an end the ancient and venerable Republic of Venice, six local stonemasons were commissioned to carry out a rather curious task. On the orders of the new authorities, the men were instructed to remove from public places 'all lions which may be considered devices or arms symbolic of the former government...' This was a clear reference to the Leone Marciano. For the next few months, the six stonemasons duly chiselled away, destroying all traces of (by their own estimate) the 1,000 book-toting beasts, which fell within their remit. Venice bears numerous scars of its long-lost lions. Well-heads were particularly badly hit. The only public well-head to survive with its Leone Marciano intact can be found in the secluded Campiello de Ca' Bernardo. Occasionally a destroyed lion was later replaced, as we can see on one of the walls of the Arsenale. The plaque makes reference to that fateful year, 1797. |