- Home

- Walking Tours

- Blog

-

St Peter's Basilica

- Altars

- Baldacchino

- Chair of St Peter

- Chapel of the Baptistery

- Chapel of the Bl. Sacrament

- Chapel of the Choir

- Chapel of the Pieta

- Crossing >

- Dome

-

Monuments

>

- Countess Matilda of Canossa

- Maria Clementina Sobieska

- Queen Christina of Sweden

- Pope Innocent VIII

- Pope Paul III

- Pope Gregory XIII

- Pope Gregory XIV

- Pope Leo XI

- Pope Urban VIII

- Pope Alexander VII

- Pope Clement X

- Pope Innocent XI

- Pope Alexander VIII

- Pope Innocent XII

- Pope Benedict XIV

- Pope Clement XIII

- Pope Pius VII

- Pope Leo XII

- Pope Pius VIII

- Pope Gregory XVI

- Pope Pius X

- Pope Benedict XV

- Pope Pius XI

- Pope Pius XII

- Pope John XXIII

- The Stuarts

- Nave

- Portico >

- Statue of St Peter

- Statues of Founder Saints

- Transept

- Tribune

- St Peter's Square

- Vatican Museums

- Sistine Chapel

-

Fountains

- Trevi Fountain

- Fontana della Barcaccia

- Fontana della Peschiera

- Fountain in Piazza Colonna

- Fountain in Piazza delle Cinque Scole

- Fountain in Piazza dell' Aracoeli

- Fountain in Piazza Nicosia

- Fountain in Piazza di S.M. in Trastevere

- Fountain of Moses

- Fountain of Neptune

- Fountains of Piazza Farnese

- Fountain of Ponte Sisto

- Fountain of the Acqua Paola

- Fountain of the Bees

- Fountain of the Cannonball

- Fountain of the Frogs

- Fountain of the Four Rivers

- Fountain of the Goddess Roma

- Fountain of the Lateran Obelisk

- Fountain of the Mask

- Fountain of the Moor

- Fountain of the Naiads

- Fountain of the Pantheon

- Fountains of Piazza del Popolo

- Fountain of the Porter

- Fountains of St Peter's Square

- Fountain of the Seahorses

- Fountain of the Triton

- Fountain of the Turtles

- Fountains of the Two Seas

- Four Fountains

- Rioni Fountains

- Street Fountains

- Venice Marries the Sea

- On This Day in Rome

-

Churches

- Chiesa del Gesù >

- Chiesa Nuova

- Lateran Baptistery

- San Bartolomeo all' Isola

- San Benedetto in Piscinula

- San Bernardo alle Terme

- San Carlo ai Catinari

- San Carlo al Corso

- San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane

- San Clemente >

- San Crisogono

- San Francesco a Ripa >

- San Giorgio in Velabro

- San Giovanni a Porta Latina

- San Giovanni dei Fiorentini

- San Giovanni in Laterano >

- San Girolamo della Carità >

- San Gregorio Magno

- San Lorenzo fuori le Mura

- San Lorenzo in Damaso

- San Lorenzo in Lucina

- San Luigi dei Francesi >

- San Marcello al Corso

- San Marco

- San Martino ai Monti

- San Nicola in Carcere

- San Pancrazio

- San Paolo fuori le Mura

- San Pietro in Montorio

- San Pietro in Vincoli

- San Saba

- San Salvatore in Lauro

- San Sebastiano fuori le Mura >

- San Silvestro in Capite

- San Vitale

- Sant' Agnese fuori le Mura

- Sant' Agnese in Agone

- Sant' Agostino

- Sant' Alessio

- Sant' Anastasia

- Sant' Andrea al Quirinale

- Sant' Andrea della Valle

- Sant' Andrea delle Fratte

- Sant' Antonio dei Portoghesi

- Sant' Apollinare

- Sant' Eustachio

- Sant' Ignazio di Loyola

- Sant' Ivo alla Sapienza

- Santa Caterina dei Funari

- Santa Cecilia in Trastevere

- Santa Costanza

- Santa Croce in Gerusalemme >

- Santa Francesca Romana

- Santa Maria ad Martyres

- Santa Maria degli Angeli

- Santa Maria dei Miracoli

- Santa Maria del Popolo >

- Santa Maria del Priorato

- Santa Maria della Pace >

- Santa Maria della Vittoria >

- Santa Maria dell' Anima

- Santa Maria dell' Orazione e Morte

- Santa Maria dell' Orto

- Santa Maria di Loreto

- Santa Maria in Aracoeli >

- Santa Maria in Campitelli

- Santa Maria in Cosmedin

- Santa Maria in Domnica

- Santa Maria in Montesanto

- Santa Maria in Trastevere >

- Santa Maria in Via

- Santa Maria in Via Lata

- Santa Maria Maddalena

- Santa Maria Maggiore >

- Santa Maria sopra Minerva >

- Santa Prassede

- Santa Pudenziana

- Santa Sabina >

- Santa Susanna

- Santi Apostoli

- Santi Cosma e Damiano

- Santi Domenico e Sisto

- Santi Giovanni e Paolo

- Santi Luca e Martina

- Santi Nereo e Achilleo

- Santi Quattro Coronati

- Santi Vincenzo e Anastasio

- Santissima Trinità degli Spagnoli

- Santissima Trinità dei Pellegrini

- Santissima Trinità di Monti

- Santissimo Nome di Maria

- Santo Stefano Rotondo

- Palatine

- Forum

-

Ancient Monuments

- Aqueducts

- Ara Pacis

- Arch of Constantine

- Arch of the Money-Changers

- Arch of Janus

- Aurelian Walls

- Baths of Caracalla

- Baths of Diocletian

- Castel Sant' Angelo

- Catacombs of Domitilla

- Circus Maxentius

- Circus Maximus

- Colosseum

- Column of Marcus Aurelius

- Column of Trajan

- Forum of Augustus

- Forum of Trajan

- Mausoleum of Augustus

- Nymphaeum

- Pantheon

- Ponte Fabricio

- Ponte Milvio

- Ponte Rotto

- Ponte Sant' Angelo

- Porta Maggiore

- Porta San Paolo

- Porta San Sebastiano

- Portico of Octavia

- Pyramid of Cestius

- Temple of Hadrian

- Temple of Hercules

- Temple of Portunus

- Theatre of Balbus

- Theatre of Marcellus

- Theatre of Pompey

- Tomb of Caecilia Metella

- Via Appia

-

Obelisks

- 'Minerveo' Obelisk

- 'Flaminio' Obelisk

- 'Matteiano' Obelisk

- 'Lateran' Obelisk

- 'Dogali' Obelisk

- 'Macuteo' Obelisk

- 'Solare' Obelisk

- 'Vatican' Obelisk

- 'Agonalis' Obelisk

- 'Sallustiano' Obelisk

- 'Quirinale' Obelisk

- 'Esquiline' Obelisk

- 'Pinciano' Obelisk

- 'Mediceo' Obelisk

- 'Torlonia' Obelisks

- 'Mussolini' Obelisk

- 'Marconi' Obelisk

-

Mosaics

- Gallery

- Palazzi

- Galleries & Museums

- Piazzas

-

Miscellaneous

- A Calendar of Saints

- A Literary Tour

- Antico Caffè Greco

- Art of the Cosmati

- Babington's Tea Rooms

- Barberini Bees

- Gian Lorenzo Bernini

- Borromini & the Baroque

- Catacombs

- Column of the Immaculate Conception

- Domes

- Equestrian Statues

- EUR

- Fasces

- Flood Plaques

- Funerary Monuments

- House of the Owls

- Jewish Ghetto

- Jubilee Years

- Knights of Malta

- Mithraism

- Monumental Complex of S. Spirito in Sassia

- Ponte Sisto

- Porta Pia

- 'Protestant' Cemetery

- Quartiere Coppedè

- Scala Santa

- Spanish Steps

- 'Talking' Statues

- Tiber Island

- Villa Borghese

- Vittoriano

- Rioni

- On This Day in Italy

-

Pictures from Italy

-

Florence

>

- A Literary Tour

- Anna Maria Luisa: Last of the Medici

- Casa-Galleria Vichi

- Column of Justice

- Column of St Zenobius

- Cosimo I de' Medici

- Cosimo II de' Medici

- Costanza Bonarelli

- David With Fig Leaf

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning

- Equestrian Statue of Cosimo I de' Medici

- Equestrian Statue of Ferdinando I de' Medici

- Festina Lente

- Floods

- Fontana del Bacchino

- Fontana dei Puttini

- Fountain of Neptune

- Fountains of the Marine Monsters

- Gian Gastone de' Medici

- Girolamo Savonarola

- Images of the Annunciation

- Little Devil

- Monument to Cellini

- Palazzo Bartolini-Salimbeni

- Palazzo Bianca Cappello

- Palazzo Fenzi

- Palazzo Viviani

- Perseus and Medusa

- Piazza Santa Maria Novella

- Pope Leo XI

- Porta della Mandorla

- Rape of the Sabine Woman

- Santa Maria Novella

- Canons' Palace

- Statue of Dante

- Theft of the Century

- Torre del Arnolfo

- Twelve Good Men

- Villa Gamberaia

- Wheel of the Innocents

- 'Wine Windows'

- Lazio >

- Tuscany >

-

Venice

>

- Ab Urbe Condita

- Acqua Alta

- Bartolomeo Colleoni

- Barque of Dante

- Burano

- Caffè Florian

- Daniele Manin

- Flagpoles

- Giustina Rossi

- Gondolas

- Harry's Bar

- Henry James

- House of Three Eyes

- King Victor Emmanuel II

- Map of Venice

- Martinmas

- Master of the House

- Palazzo Contarini Fasan

- Ponte Borgoloco

- Ponte Chiodo

- Punta del Dogana

- Scacciadiavoli

- Shrine of St Lucia

- Sior Antonio Rioba

- The 'Book Shitter'

- The Lion's Mouth

- Tommaso Rangone

- Torcello

- Venus

- 'Viennese Oranges'

- Wellheads

- Winged Lions

-

Florence

>

- Popes: 1417-Present

- Cloisters

Santa Maria del Popolo

According to legend, the church of Santa Maria del Popolo stands on the site of the tomb of the emperor Nero (r. 54-68). For centuries the local populace was convinced the area was haunted by Nero’s ghost and that the large, black crows, which roosted in a nearby walnut tree, were his evil familiars. In 1099 the newly elected pope, Paschal II (r. 1099-1118), decided to put an end to such superstitions by having the tree felled. The Pope then made sure the area remained free of evil spirits by building an oratory on the site.

In time the oratory was enlarged into a church, which, since 1250, has belonged to the Augustinian friars. It was in the monastery, which was once attached to the church, that Martin Luther stayed during his visit to Rome in 1511.

Between 1472 and 1478 the church took on the form we see today. The architect was Baccio Pontelli (1450-92), who rebuilt the church on the instructions of Pope Sixtus IV (r. 1471-84). Santa Maria del Popolo has a simple yet dignified Renaissance façade, the work, some think, of Andrea Bregno (1418-1506). The two side doors have lintels inscribed with the name of Pope Sixtus IV, but the one on the left is mis-spelt!

Santa Maria del Popolo might be a small church, but it is one which punches well above its weight. The list of architects, sculptors and painters who worked there reads like a roll-call of famous figures from the Renaissance and the Baroque.

Between 1472 and 1478 the church took on the form we see today. The architect was Baccio Pontelli (1450-92), who rebuilt the church on the instructions of Pope Sixtus IV (r. 1471-84). Santa Maria del Popolo has a simple yet dignified Renaissance façade, the work, some think, of Andrea Bregno (1418-1506). The two side doors have lintels inscribed with the name of Pope Sixtus IV, but the one on the left is mis-spelt!

Santa Maria del Popolo might be a small church, but it is one which punches well above its weight. The list of architects, sculptors and painters who worked there reads like a roll-call of famous figures from the Renaissance and the Baroque.

The church retains much of its original design in the arcades of the nave, which is made up of four pillars on either side. Two centuries later, Gian Lorenzo Bernini added the statues of female saints to the arches of the nave. Each saint, the work of pupils and not the master, is identified by an inscription in the spandrels of the arches. The work was carried out during the reign of Alexander VII (r. 1655-67), whose coat of arms adorns the triumphal arch.

The high altar is the work of Bernini and replaces the one designed in the Renaissance style by Andrea Bregno, which can now be found in the sacristy. The broken pediments are crowned by a group of angels and putti, the outer pair of which are waving. The icon of the Virgin and Child, known as the Madonna del Popolo, is thought to date from the 12th or 13th centuries.

The choir, which is normally out of bounds, was designed by Bramante between 1500 and 1509 for Pope Julius II (r. 1503-13). Here we find the funerary monuments of cardinals Ascanio Sforza and Girolamo Basso della Rovere, both the work of Andrea Sansovino (1467-1529). They are among the most important Renaissance sculptures in Rome. Both effigies are depicted reclining half-asleep, a marked departure from the medieval practise, which portrayed the dead more formally, lying in state.

The stained glass windows, the work of the French artist Guillame de Marcillat (c. 1470-1529), are the oldest in Rome. The windows depict scenes from the childhood of Christ on one wall and the life of the Virgin Mary on the other. The vault of the choir was painted by Bernardino di Betto (1454-1513), better known as il Pinturicchio, and depicts, in the centre, the Coronation of the Virgin Mary.

The stained glass windows, the work of the French artist Guillame de Marcillat (c. 1470-1529), are the oldest in Rome. The windows depict scenes from the childhood of Christ on one wall and the life of the Virgin Mary on the other. The vault of the choir was painted by Bernardino di Betto (1454-1513), better known as il Pinturicchio, and depicts, in the centre, the Coronation of the Virgin Mary.

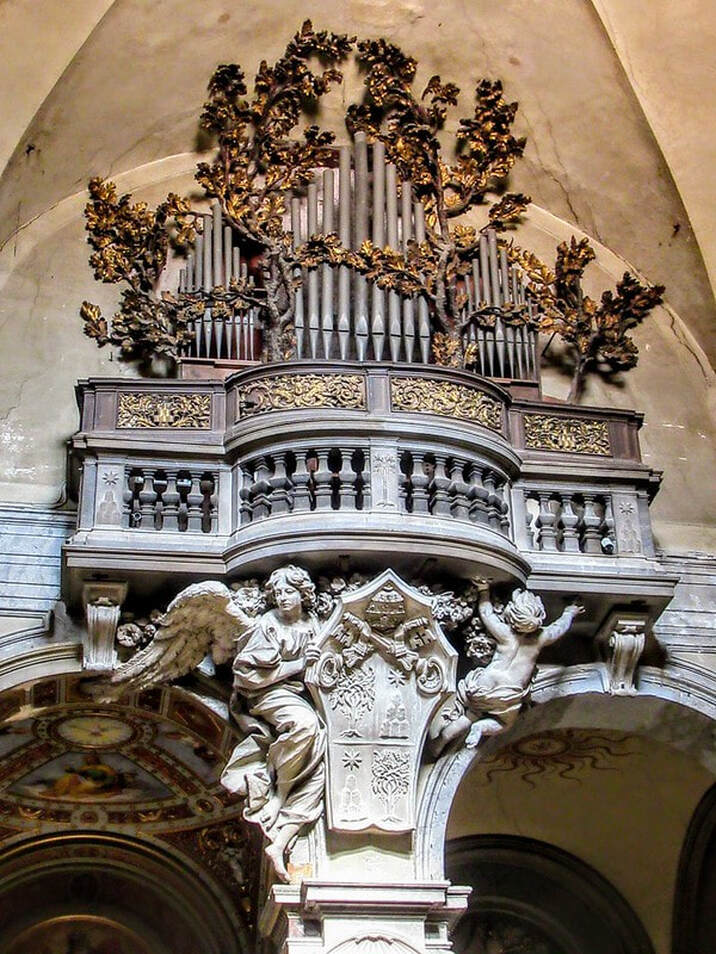

The organ in the right transept is festooned with bronze oak branches, the idea of Bernini and a reference to the Chigi coat of arms. The beautiful organ loft is the work of one of Bernini’s more talented pupils, Antonio Raggi.

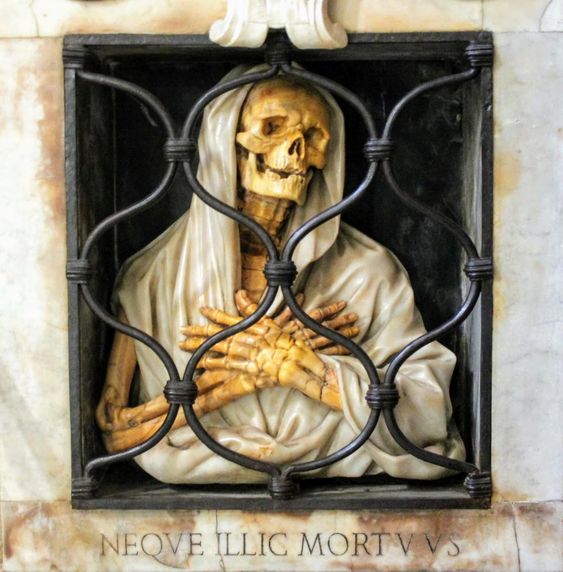

Santa Maria del Popolo is full of tombs. There are tombs in the floor, tombs resting against the columns, tombs galore in the chapels. Tombs seem to be squeezed into every nook and cranny of the church. A much-photographed funerary monument

lies to the left of the main entrance and belongs to Giovanni Battista Gisleni, a little-known Roman architect, who died in 1672.

A short distance away, to the left of the Chigi Chapel (second bay of the left aisle), is one of the most curious funerary monuments in the whole of Rome. It records the early death, in childbirth, of Princess Maria Federica Odescalchi-Chigi.

The Cappella Chigi was designed by Raphael (1483-1520) for his friend and patron, the wealthy banker Agostino Chigi and his brother Sigismondo, both of whom are buried here.

Santa Maria del Popolo is full of tombs. There are tombs in the floor, tombs resting against the columns, tombs galore in the chapels. Tombs seem to be squeezed into every nook and cranny of the church. A much-photographed funerary monument

lies to the left of the main entrance and belongs to Giovanni Battista Gisleni, a little-known Roman architect, who died in 1672.

A short distance away, to the left of the Chigi Chapel (second bay of the left aisle), is one of the most curious funerary monuments in the whole of Rome. It records the early death, in childbirth, of Princess Maria Federica Odescalchi-Chigi.

The Cappella Chigi was designed by Raphael (1483-1520) for his friend and patron, the wealthy banker Agostino Chigi and his brother Sigismondo, both of whom are buried here.

The third chapel off the left aisle is the Cappella Mellini, the mortuary chapel of the Mellini family. Filled to the brim with tombs, it was founded by Pietro Mellini in the 15th century. It was restored by Cardinal Giovanni Garcia Mellini in the early 17th century and his monument on the left wall is the work of Alessandro Algardi (1598-1654). Algardi was a contemporary of Bernini and the second greatest sculptor in 17th century Rome, but his portrait busts are much less flamboyant, and more understated, than those of his rival. Cardinal Mellini turns towards the altar, his left hand on his heart and his right hand marking the place in his prayer book. The portrait was much admired in Algardi’s day with many praising, in particular, the lace on the cardinal’s sleeve.

Santa Maria del Popolo is a major stop on Rome's Caravaggio trail and two of his paintings can be found in the Cappella Cerasi, which lies at the end of the left aisle. The same chapel houses the funerary monument (1857) to Teresa Pelzer, who died in childbirth. It is the work of Giuseppe Tenerani.

Santa Maria del Popolo is a major stop on Rome's Caravaggio trail and two of his paintings can be found in the Cappella Cerasi, which lies at the end of the left aisle. The same chapel houses the funerary monument (1857) to Teresa Pelzer, who died in childbirth. It is the work of Giuseppe Tenerani.

The first chapel in the right aisle is the Cappella della Rovere, which is dedicated to St Jerome and was built for Cardinal Domenico della Rovere. The family, which hailed from Savona, a town in the north west of Italy, produced two popes, Sixtus IV (r. 1471-84) and Julius II (r. 1503-13). Their emblem is an oak tree, which can be seen in the marble screen separating the chapel from the church. The altarpiece of the Nativity is by Pinturicchio, who also painted the rather faded frescoes in the lunettes. St Joseph rests his head on his left hand and looks down at the Christ Child with rather a dubious air. According to an ancient tradition, St Joseph was often tempted by the Devil to doubt the divine origin of his son!

The third chapel in the right aisle is the Cappella Basso della Rovere. The cardinal's splendid tomb was carved by pupils of Andrea Bregno. The paintings of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary and the Virgin and Child, and the five frescoes in the lunettes, are by pupils of Pinturicchio. The extremely illusionistic monochrome frescoes were also by pupils of the Umbrian master. The chapel retains some of its original floor tiles, which are made from Deruta majolica.

At the end of the right aisle, in the Cappella Costa, is the beautiful bronze effigy of Cardinal Pietro Foscari, the work of Lorenzo di Pietro (1410-80), better known as Il Vecchietta.

At the end of the right aisle, in the Cappella Costa, is the beautiful bronze effigy of Cardinal Pietro Foscari, the work of Lorenzo di Pietro (1410-80), better known as Il Vecchietta.

Gallery

- Home

- Walking Tours

- Blog

-

St Peter's Basilica

- Altars

- Baldacchino

- Chair of St Peter

- Chapel of the Baptistery

- Chapel of the Bl. Sacrament

- Chapel of the Choir

- Chapel of the Pieta

- Crossing >

- Dome

-

Monuments

>

- Countess Matilda of Canossa

- Maria Clementina Sobieska

- Queen Christina of Sweden

- Pope Innocent VIII

- Pope Paul III

- Pope Gregory XIII

- Pope Gregory XIV

- Pope Leo XI

- Pope Urban VIII

- Pope Alexander VII

- Pope Clement X

- Pope Innocent XI

- Pope Alexander VIII

- Pope Innocent XII

- Pope Benedict XIV

- Pope Clement XIII

- Pope Pius VII

- Pope Leo XII

- Pope Pius VIII

- Pope Gregory XVI

- Pope Pius X

- Pope Benedict XV

- Pope Pius XI

- Pope Pius XII

- Pope John XXIII

- The Stuarts

- Nave

- Portico >

- Statue of St Peter

- Statues of Founder Saints

- Transept

- Tribune

- St Peter's Square

- Vatican Museums

- Sistine Chapel

-

Fountains

- Trevi Fountain

- Fontana della Barcaccia

- Fontana della Peschiera

- Fountain in Piazza Colonna

- Fountain in Piazza delle Cinque Scole

- Fountain in Piazza dell' Aracoeli

- Fountain in Piazza Nicosia

- Fountain in Piazza di S.M. in Trastevere

- Fountain of Moses

- Fountain of Neptune

- Fountains of Piazza Farnese

- Fountain of Ponte Sisto

- Fountain of the Acqua Paola

- Fountain of the Bees

- Fountain of the Cannonball

- Fountain of the Frogs

- Fountain of the Four Rivers

- Fountain of the Goddess Roma

- Fountain of the Lateran Obelisk

- Fountain of the Mask

- Fountain of the Moor

- Fountain of the Naiads

- Fountain of the Pantheon

- Fountains of Piazza del Popolo

- Fountain of the Porter

- Fountains of St Peter's Square

- Fountain of the Seahorses

- Fountain of the Triton

- Fountain of the Turtles

- Fountains of the Two Seas

- Four Fountains

- Rioni Fountains

- Street Fountains

- Venice Marries the Sea

- On This Day in Rome

-

Churches

- Chiesa del Gesù >

- Chiesa Nuova

- Lateran Baptistery

- San Bartolomeo all' Isola

- San Benedetto in Piscinula

- San Bernardo alle Terme

- San Carlo ai Catinari

- San Carlo al Corso

- San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane

- San Clemente >

- San Crisogono

- San Francesco a Ripa >

- San Giorgio in Velabro

- San Giovanni a Porta Latina

- San Giovanni dei Fiorentini

- San Giovanni in Laterano >

- San Girolamo della Carità >

- San Gregorio Magno

- San Lorenzo fuori le Mura

- San Lorenzo in Damaso

- San Lorenzo in Lucina

- San Luigi dei Francesi >

- San Marcello al Corso

- San Marco

- San Martino ai Monti

- San Nicola in Carcere

- San Pancrazio

- San Paolo fuori le Mura

- San Pietro in Montorio

- San Pietro in Vincoli

- San Saba

- San Salvatore in Lauro

- San Sebastiano fuori le Mura >

- San Silvestro in Capite

- San Vitale

- Sant' Agnese fuori le Mura

- Sant' Agnese in Agone

- Sant' Agostino

- Sant' Alessio

- Sant' Anastasia

- Sant' Andrea al Quirinale

- Sant' Andrea della Valle

- Sant' Andrea delle Fratte

- Sant' Antonio dei Portoghesi

- Sant' Apollinare

- Sant' Eustachio

- Sant' Ignazio di Loyola

- Sant' Ivo alla Sapienza

- Santa Caterina dei Funari

- Santa Cecilia in Trastevere

- Santa Costanza

- Santa Croce in Gerusalemme >

- Santa Francesca Romana

- Santa Maria ad Martyres

- Santa Maria degli Angeli

- Santa Maria dei Miracoli

- Santa Maria del Popolo >

- Santa Maria del Priorato

- Santa Maria della Pace >

- Santa Maria della Vittoria >

- Santa Maria dell' Anima

- Santa Maria dell' Orazione e Morte

- Santa Maria dell' Orto

- Santa Maria di Loreto

- Santa Maria in Aracoeli >

- Santa Maria in Campitelli

- Santa Maria in Cosmedin

- Santa Maria in Domnica

- Santa Maria in Montesanto

- Santa Maria in Trastevere >

- Santa Maria in Via

- Santa Maria in Via Lata

- Santa Maria Maddalena

- Santa Maria Maggiore >

- Santa Maria sopra Minerva >

- Santa Prassede

- Santa Pudenziana

- Santa Sabina >

- Santa Susanna

- Santi Apostoli

- Santi Cosma e Damiano

- Santi Domenico e Sisto

- Santi Giovanni e Paolo

- Santi Luca e Martina

- Santi Nereo e Achilleo

- Santi Quattro Coronati

- Santi Vincenzo e Anastasio

- Santissima Trinità degli Spagnoli

- Santissima Trinità dei Pellegrini

- Santissima Trinità di Monti

- Santissimo Nome di Maria

- Santo Stefano Rotondo

- Palatine

- Forum

-

Ancient Monuments

- Aqueducts

- Ara Pacis

- Arch of Constantine

- Arch of the Money-Changers

- Arch of Janus

- Aurelian Walls

- Baths of Caracalla

- Baths of Diocletian

- Castel Sant' Angelo

- Catacombs of Domitilla

- Circus Maxentius

- Circus Maximus

- Colosseum

- Column of Marcus Aurelius

- Column of Trajan

- Forum of Augustus

- Forum of Trajan

- Mausoleum of Augustus

- Nymphaeum

- Pantheon

- Ponte Fabricio

- Ponte Milvio

- Ponte Rotto

- Ponte Sant' Angelo

- Porta Maggiore

- Porta San Paolo

- Porta San Sebastiano

- Portico of Octavia

- Pyramid of Cestius

- Temple of Hadrian

- Temple of Hercules

- Temple of Portunus

- Theatre of Balbus

- Theatre of Marcellus

- Theatre of Pompey

- Tomb of Caecilia Metella

- Via Appia

-

Obelisks

- 'Minerveo' Obelisk

- 'Flaminio' Obelisk

- 'Matteiano' Obelisk

- 'Lateran' Obelisk

- 'Dogali' Obelisk

- 'Macuteo' Obelisk

- 'Solare' Obelisk

- 'Vatican' Obelisk

- 'Agonalis' Obelisk

- 'Sallustiano' Obelisk

- 'Quirinale' Obelisk

- 'Esquiline' Obelisk

- 'Pinciano' Obelisk

- 'Mediceo' Obelisk

- 'Torlonia' Obelisks

- 'Mussolini' Obelisk

- 'Marconi' Obelisk

-

Mosaics

- Gallery

- Palazzi

- Galleries & Museums

- Piazzas

-

Miscellaneous

- A Calendar of Saints

- A Literary Tour

- Antico Caffè Greco

- Art of the Cosmati

- Babington's Tea Rooms

- Barberini Bees

- Gian Lorenzo Bernini

- Borromini & the Baroque

- Catacombs

- Column of the Immaculate Conception

- Domes

- Equestrian Statues

- EUR

- Fasces

- Flood Plaques

- Funerary Monuments

- House of the Owls

- Jewish Ghetto

- Jubilee Years

- Knights of Malta

- Mithraism

- Monumental Complex of S. Spirito in Sassia

- Ponte Sisto

- Porta Pia

- 'Protestant' Cemetery

- Quartiere Coppedè

- Scala Santa

- Spanish Steps

- 'Talking' Statues

- Tiber Island

- Villa Borghese

- Vittoriano

- Rioni

- On This Day in Italy

-

Pictures from Italy

-

Florence

>

- A Literary Tour

- Anna Maria Luisa: Last of the Medici

- Casa-Galleria Vichi

- Column of Justice

- Column of St Zenobius

- Cosimo I de' Medici

- Cosimo II de' Medici

- Costanza Bonarelli

- David With Fig Leaf

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning

- Equestrian Statue of Cosimo I de' Medici

- Equestrian Statue of Ferdinando I de' Medici

- Festina Lente

- Floods

- Fontana del Bacchino

- Fontana dei Puttini

- Fountain of Neptune

- Fountains of the Marine Monsters

- Gian Gastone de' Medici

- Girolamo Savonarola

- Images of the Annunciation

- Little Devil

- Monument to Cellini

- Palazzo Bartolini-Salimbeni

- Palazzo Bianca Cappello

- Palazzo Fenzi

- Palazzo Viviani

- Perseus and Medusa

- Piazza Santa Maria Novella

- Pope Leo XI

- Porta della Mandorla

- Rape of the Sabine Woman

- Santa Maria Novella

- Canons' Palace

- Statue of Dante

- Theft of the Century

- Torre del Arnolfo

- Twelve Good Men

- Villa Gamberaia

- Wheel of the Innocents

- 'Wine Windows'

- Lazio >

- Tuscany >

-

Venice

>

- Ab Urbe Condita

- Acqua Alta

- Bartolomeo Colleoni

- Barque of Dante

- Burano

- Caffè Florian

- Daniele Manin

- Flagpoles

- Giustina Rossi

- Gondolas

- Harry's Bar

- Henry James

- House of Three Eyes

- King Victor Emmanuel II

- Map of Venice

- Martinmas

- Master of the House

- Palazzo Contarini Fasan

- Ponte Borgoloco

- Ponte Chiodo

- Punta del Dogana

- Scacciadiavoli

- Shrine of St Lucia

- Sior Antonio Rioba

- The 'Book Shitter'

- The Lion's Mouth

- Tommaso Rangone

- Torcello

- Venus

- 'Viennese Oranges'

- Wellheads

- Winged Lions

-

Florence

>

- Popes: 1417-Present

- Cloisters